Santez Bega

Un article de GrandTerrier.

1 Fiche signalétique

|

2 Almanach

| ||||||||||||||||||||

3 Sources

|

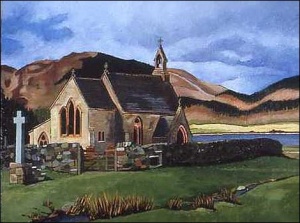

4 Iconographie | ||||||||||||||||||||

5 Monographies

Site en.Wikipedia :

Saint Bega

Note: There is a similarly named Saint Begga not to be confused with Saint Bega.

St. Bega also known as St. Bee was reputedly a Dark Ages' saint of what is now north-west England, the area at the time being part of the Celtic kingdom of Rheged.[citation needed]

She was supposedly an Irish king's daughter[1] who valued virginity. She was said to be promised in marriage to a Viking prince who, according to a medieval manuscript, was "son of the king of Norway". Bega "fled across the Irish sea to land at what in now called St. Bees, a remote spot on the Cumbrian coast. There she settled for a time, leading a life of exemplary piety. Then, fearing the raids of pirates which were starting along the coast, she moved over to Northumbria."

She was associated in legend with a number of miracles, the most famous being the "Snow miracle":

Ranulf le Meschin (sic) had endowed the monastery with its lands, but a lawsuit later developed about their extent. The monks feared a miscarriage of justice. The day appointed for a perambulation of the boundaries arrived - and, lo and behold, there was a thick snowfall on all the surrounding lands but not a flake upon the lands of the priory.

The Venerable Bede and the author of a derivative thirteenth-century account both identified St Bega as the abbess of Hartlepool and as a real-life person who supposedly flourished in the late 7th Century AD. Melvyn Bragg wrote the novel Credo based on her life as accounted by these sources. However, the dates given by Bede do not appear to be consistent with the dates normally assumed for the founder of the community at St. Bees - for which the most likely date is about 850 AD.

The discovery of inconsistencies between these medieval texts, coupled with the significance attached to her jewellery (said to have been left in Cumbria on her departure for the north-east), now indicate that the abbess never existed. ... More plausible is the suggestion that St Bega was the personification of a Cumbrian cult centred on ‘her’ bracelet (Old English: beag). [2]

The latest edition of the Dictionary of National Biography includes an article (by Professor Robert Bartlett) that treats St Bega only as a mythical figure. Most of those Christians who still venerate St Bega/St Bee disagree with this interpretation.

The name Kilbucho in Scotland is also a dedication to her.

References

- . ^ Bartlett, Robert. "Britain and Ireland, 900-1300: Insular Responses to Medieval European Change". (Cambridge, England): Cambridge University Press, 1999. p. 71.

- . ^ Myth, legend, and mystery in the Oxford DNB, Philip Carter

Site Early British Kingdoms :

St. Bega, Prioress of Copeland (Died AD 681)

The legend is that St. Bega, commonly called St. Bee of Egremont, was the daughter of an Irish king and was the most beautiful woman in her country. She was to be married to the King of Norway, but she had, from her infancy, vowed herself to a religious ascetic life and, in token of her betrothal to Christ, had received, from an angel, a bracelet marked with the sign of the cross. The night before her wedding-day, while the guards and attendants were revelling or sleeping, she fled, taking the bracelet with her. Finding no ship to speed her escape, she cut a turf from the ground and, on it, crossed the Irish Sea to the English Coast opposite. She landed on a promontory - thenceforth called St. Bee's Head - in Cumberland, then part of the Kingdom of Northumbria. She lived there, in prayer and charity, as a hermit, fed by the wild birds, but with an increase in piratical raids, she was advised by King Oswald to enter the safety of a nunnery. She received the veil from St. Aidan, Bishop of Northumbria and travelled the district, preaching at places such as Kilbees in Scotland, before founding the nunnery of Copeland Priory, near Carlisle, as well as "St. Bee's" around her old hermitage. She is said to have cooked, washed and mended for the workmen who erected its buildings.

In the Middle Ages, she was especially appealed to against oppressors of the poor, to whom she had been devoted in her lifetime, and against Scottish Border Rievers. She was Patroness of the north-west of England and also of Norway. In the 12th century, her bracelet was kept at St. Bees as a holy relic on which persons were called upon to swear, as it was believed that a false oath made on that relic would be immediately exposed and incur a dreadful vengeance.

Some say that St. Bega moved even further inland and finally settled on the opposite coast of Northumbria, where Northern Christianity was centred and protected. On this supposition, she is identified, by some authorities - amongst them the Aberdeen Breviary - with St. Begu of Hackness and St. Heiu of Hartlepool. This is unlikely as all three appear to be distinct personages. In fact, St. Bega's name is so close to the Anglo-Saxon word for a bracelet - beag - that it seems likely that she was conjured up from the reverence afforded to her holiest relic. Her feast day is usually given as 31st October, but this appears to be due to confusion with St. Begu of Hackness.

Partly edited from Agnes Dunbar's "A Dictionary of Saintly Women" (1904).